Continuum mechanics

| Continuum mechanics |

|---|

Continuum mechanics is a branch of mechanics that deals with the analysis of the kinematics and the mechanical behavior of materials modelled as a continuous mass rather than as discrete particles. The French mathematician Augustin Louis Cauchy was the first to formulate such models in the 19th century, but research in the area continues today.

Modelling an object as a continuum assumes that the substance of the object completely fills the space it occupies. Modelling objects in this way ignores the fact that matter is made of atoms, and so is not continuous; however, on length scales much greater than that of inter-atomic distances, such models are highly accurate. Fundamental physical laws such as the conservation of mass, the conservation of momentum, and the conservation of energy may be applied to such models to derive differential equations describing the behavior of such objects, and some information about the particular material studied is added through a constitutive relation.

Continuum mechanics deals with physical properties of solids and fluids which are independent of any particular coordinate system in which they are observed. These physical properties are then represented by tensors, which are mathematical objects that have the required property of being independent of coordinate system. These tensors can be expressed in coordinate systems for computational convenience.

Contents |

Concept of a continuum

Materials, such as solids, liquids and gases, are composed of molecules separated by empty space. On a macroscopic scale, materials have cracks and discontinuities. However, certain physical phenomena can be modelled assuming the materials exist as a continuum, meaning the matter in the body is continuously distributed and fills the entire region of space it occupies. A continuum is a body that can be continually sub-divided into infinitesimal elements with properties being those of the bulk material.

The validity of the continuum assumption may be verified by a theoretical analysis, in which either some clear periodicity is identified or statistical homogeneity and ergodicity of the microstructure exists. More specifically, the continuum hypothesis/assumption hinges on the concepts of a representative volume element (RVE) (sometimes called "representative elementary volume") and separation of scales based on the Hill–Mandel condition. This condition provides a link between an experimentalist's and a theoretician's viewpoint on constitutive equations (linear and nonlinear elastic/inelastic or coupled fields) as well as a way of spatial and statistical averaging of the microstructure.[1]

When the separation of scales does not hold, or when one wants to establish a continuum of a finer resolution than that of the RVE size, one employs a statistical volume element (SVE), which, in turn, leads to random continuum fields. The latter then provide a micromechanics basis for stochastic finite elements (SFE). The levels of SVE and RVE link continuum mechanics to statistical mechanics. The RVE may be assessed only in a limited way via experimental testing: when the constitutive response becomes spatially homogeneous.

Specifically for fluids, the Knudsen number is used to assess to what extent the approximation of continuity can be made.

Major areas of continuum mechanics

| Continuum mechanics The study of the physics of continuous materials |

Solid mechanics The study of the physics of continuous materials with a defined rest shape. |

Elasticity Describes materials that return to their rest shape after an applied stress. |

|

| Plasticity Describes materials that permanently deform after a sufficient applied stress. |

Rheology The study of materials with both solid and fluid characteristics. |

||

| Fluid mechanics The study of the physics of continuous materials which take the shape of their container. |

Non-Newtonian fluids | ||

| Newtonian fluids | |||

Formulation of models

Continuum mechanics models begin by assigning a region in three dimensional Euclidean space to the material body  being modeled. The points within this region are called particles or material points. Different configurations or states of the body correspond to different regions in Euclidean space. The region corresponding to the body's configuration at time

being modeled. The points within this region are called particles or material points. Different configurations or states of the body correspond to different regions in Euclidean space. The region corresponding to the body's configuration at time  is labeled

is labeled  .

.

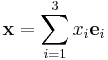

A particular particle within the body in a particular configuration is characterized by a position vector

,

,

where  are the coordinate vectors in some frame of reference chosen for the problem (See figure 1). This vector can be expressed as a function of the particle position

are the coordinate vectors in some frame of reference chosen for the problem (See figure 1). This vector can be expressed as a function of the particle position  in some reference configuration, for example the configuration at the initial time, so that

in some reference configuration, for example the configuration at the initial time, so that

.

.

This function needs to have various properties so that the model makes physical sense.  needs to be:

needs to be:

- continuous in time, so that the body changes in a way which is realistic,

- globally invertible at all times, so that the body cannot intersect itself,

- orientation-preserving, as transformations which produce mirror reflections are not possible in nature.

For the mathematical formulation of the model,  is also assumed to be twice continuously differentiable, so that differential equations describing the motion may be formulated.

is also assumed to be twice continuously differentiable, so that differential equations describing the motion may be formulated.

Forces in a continuum

Continuum mechanics deals with deformable bodies, as opposed to rigid bodies. A solid is a deformable body that possesses shear strength, sc. a solid can support shear forces (forces parallel to the material surface on which they act). Fluids, on the other hand, do not sustain shear forces. For the study of the mechanical behavior of solids and fluids these are assumed to be continuous bodies, which means that the matter fills the entire region of space it occupies, despite the fact that matter is made of atoms, has voids, and is discrete. Therefore, when continuum mechanics refers to a point or particle in a continuous body it does not describe a point in the interatomic space or an atomic particle, rather an idealized part of the body occupying that point.

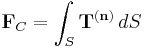

Following the classical dynamics of Newton and Euler, the motion of a material body is produced by the action of externally applied forces which are assumed to be of two kinds: surface forces  and body forces

and body forces  .[2] Thus, the total force

.[2] Thus, the total force  applied to a body or to a portion of the body can be expressed as:

applied to a body or to a portion of the body can be expressed as:

Surface forces or contact forces, expressed as force per unit area, can act either on the bounding surface of the body, as a result of mechanical contact with other bodies, or on imaginary internal surfaces that bound portions of the body, as a result of the mechanical interaction between the parts of the body to either side of the surface (Euler-Cauchy's stress principle). When a body is acted upon by external contact forces, internal contact forces are then transmitted from point to point inside the body to balance their action, according to Newton's second law of motion of conservation of linear momentum and angular momentum (for continuous bodies these laws are called the Euler's equations of motion). The internal contact forces are related to the body's deformation through constitutive equations. The internal contact forces may be mathematically described by how they relate to the motion of the body, independent of the body's material makeup.[3]

The distribution of internal contact forces throughout the volume of the body is assumed to be continuous. Therefore, there exists a contact force density or Cauchy traction field [2]  that represents this distribution in a particular configuration of the body at a given time

that represents this distribution in a particular configuration of the body at a given time  . It is not a vector field because it depends not only on the position

. It is not a vector field because it depends not only on the position  of a particular material point, but also on the local orientation of the surface element as defined by its normal vector

of a particular material point, but also on the local orientation of the surface element as defined by its normal vector  .[4]

.[4]

Any differential area  with normal vector

with normal vector  of a given internal surface area

of a given internal surface area  , bounding a portion of the body, experiences a contact force

, bounding a portion of the body, experiences a contact force  arising from the contact between both portions of the body on each side of

arising from the contact between both portions of the body on each side of  , and it is given by

, and it is given by

where  is the surface traction,[5] also called stress vector,[6] traction,[7] or traction vector.[8] The stress vector is a frame-indifferent vector (see Euler-Cauchy's stress principle).

is the surface traction,[5] also called stress vector,[6] traction,[7] or traction vector.[8] The stress vector is a frame-indifferent vector (see Euler-Cauchy's stress principle).

The total contact force on the particular internal surface  is then expressed as the sum (surface integral) of the contact forces on all differential surfaces

is then expressed as the sum (surface integral) of the contact forces on all differential surfaces  :

:

In continuum mechanics a body is considered stress-free if the only forces present are those inter-atomic forces (ionic, metallic, and van der Waals forces) required to hold the body together and to keep its shape in the absence of all external influences, including gravitational attraction.[8][9] Stresses generated during manufacture of the body to a specific configuration are also excluded when considering stresses in a body. Therefore, the stresses considered in continuum mechanics are only those produced by deformation of the body, sc. only relative changes in stress are considered, not the absolute values of stress.

Body forces are forces originating from sources outside of the body[10] that act on the volume (or mass) of the body. Saying that body forces are due to outside sources implies that the interaction between different parts of the body (internal forces) are manifested through the contact forces alone.[5] These forces arise from the presence of the body in force fields, e.g. gravitational field (gravitational forces) or electromagnetic field (electromagnetic forces), or from inertial forces when bodies are in motion. As the mass of a continuous body is assumed to be continuously distributed, any force originating from the mass is also continuously distributed. Thus, body forces are specified by vector fields which are assumed to be continuous over the entire volume of the body,[11] i.e. acting on every point in it. Body forces are represented by a body force density  (per unit of mass), which is a frame-indifferent vector field.

(per unit of mass), which is a frame-indifferent vector field.

In the case of gravitational forces, the intensity of the force depends on, or is proportional to, the mass density  of the material, and it is specified in terms of force per unit mass (

of the material, and it is specified in terms of force per unit mass ( ) or per unit volume (

) or per unit volume ( ). These two specifications are related through the material density by the equation

). These two specifications are related through the material density by the equation  . Similarly, the intensity of electromagnetic forces depends upon the strength (electric charge) of the electromagnetic field.

. Similarly, the intensity of electromagnetic forces depends upon the strength (electric charge) of the electromagnetic field.

The total body force applied to a continuous body is expressed as

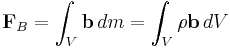

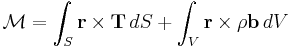

Body forces and contact forces acting on the body lead to corresponding moments of force (torques) relative to a given point. Thus, the total applied torque  about the origin is given by

about the origin is given by

In certain situations, not commonly considered in the analysis of the mechanical behavior or materials, it becomes necessary to include two other types of forces: these are body moments and couple stresses[12][13] (surface couples,[10] contact torques[11]). Body moments, or body couples, are moments per unit volume or per unit mass applied to the volume of the body. Couple stresses are moments per unit area applied on a surface. Both are important in the analysis of stress for a polarized dielectric solid under the action of an electric field, materials where the molecular structure is taken into consideration (e.g. bones), solids under the action of an external magnetic field, and the dislocation theory of metals.[6][7][10]

Materials that exhibit body couples and couple stresses in addition to moments produced exclusively by forces are called polar materials.[7][11] Non-polar materials are then those materials with only moments of forces. In the classical branches of continuum mechanics the development of the theory of stresses is based on non-polar materials.

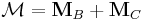

Thus, the sum of all applied forces and torques (with respect to the origin of the coordinate system) in the body can be given by

Kinematics: deformation and motion

A change in the configuration of a continuum body results in a displacement. The displacement of a body has two components: a rigid-body displacement and a deformation. A rigid-body displacement consists of a simultaneous translation and rotation of the body without changing its shape or size. Deformation implies the change in shape and/or size of the body from an initial or undeformed configuration  to a current or deformed configuration

to a current or deformed configuration  (Figure 2).

(Figure 2).

The motion of a continuum body is a continuous time sequence of displacements. Thus, the material body will occupy different configurations at different times so that a particle occupies a series of points in space which describe a pathline.

There is continuity during deformation or motion of a continuum body in the sense that:

- The material points forming a closed curve at any instant will always form a closed curve at any subsequent time.

- The material points forming a closed surface at any instant will always form a closed surface at any subsequent time and the matter within the closed surface will always remain within.

It is convenient to identify a reference configuration or initial condition which all subsequent configurations are referenced from. The reference configuration need not be one that the body will ever occupy. Often, the configuration at  is considered the reference configuration,

is considered the reference configuration,  . The components

. The components  of the position vector

of the position vector  of a particle, taken with respect to the reference configuration, are called the material or reference coordinates.

of a particle, taken with respect to the reference configuration, are called the material or reference coordinates.

When analyzing the deformation or motion of solids, or the flow of fluids, it is necessary to describe the sequence or evolution of configurations throughout time. One description for motion is made in terms of the material or referential coordinates, called material description or Lagrangian description.

Lagrangian description

In the Lagrangian description the position and physical properties of the particles are described in terms of the material or referential coordinates and time. In this case the reference configuration is the configuration at  . An observer standing in the referential frame of reference observes the changes in the position and physical properties as the material body moves in space as time progresses. The results obtained are independent of the choice of initial time and reference configuration,

. An observer standing in the referential frame of reference observes the changes in the position and physical properties as the material body moves in space as time progresses. The results obtained are independent of the choice of initial time and reference configuration,  . This description is normally used in solid mechanics.

. This description is normally used in solid mechanics.

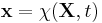

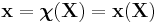

In the Lagrangian description, the motion of a continuum body is expressed by the mapping function  (Figure 2),

(Figure 2),

which is a mapping of the initial configuration  onto the current configuration

onto the current configuration  , giving a geometrical correspondence between them, i.e. giving the position vector

, giving a geometrical correspondence between them, i.e. giving the position vector  that a particle

that a particle  , with a position vector

, with a position vector  in the undeformed or reference configuration

in the undeformed or reference configuration  , will occupy in the current or deformed configuration

, will occupy in the current or deformed configuration  at time

at time  . The components

. The components  are called the spatial coordinates.

are called the spatial coordinates.

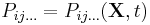

Physical and kinematic properties  , i.e. thermodynamic properties and velocity, which describe or characterize features of the material body, are expressed as continuous functions of position and time, i.e.

, i.e. thermodynamic properties and velocity, which describe or characterize features of the material body, are expressed as continuous functions of position and time, i.e.  .

.

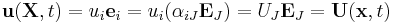

The material derivative of any property  of a continuum, which may be a scalar, vector, or tensor, is the time rate of change of that property for a specific group of particles of the moving continuum body. The material derivative is also known as the substantial derivative, or comoving derivative, or convective derivative. It can be thought as the rate at which the property changes when measured by an observer traveling with that group of particles.

of a continuum, which may be a scalar, vector, or tensor, is the time rate of change of that property for a specific group of particles of the moving continuum body. The material derivative is also known as the substantial derivative, or comoving derivative, or convective derivative. It can be thought as the rate at which the property changes when measured by an observer traveling with that group of particles.

In the Lagrangian description, the material derivative of  is simply the partial derivative with respect to time, and the position vector

is simply the partial derivative with respect to time, and the position vector  is held constant as it does not change with time. Thus, we have

is held constant as it does not change with time. Thus, we have

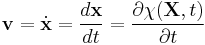

The instantaneous position  is a property of a particle, and its material derivative is the instantaneous velocity

is a property of a particle, and its material derivative is the instantaneous velocity  of the particle. Therefore, the velocity field of the continuum is given by

of the particle. Therefore, the velocity field of the continuum is given by

Similarly, the acceleration field is given by

Continuity in the Lagrangian description is expressed by the spatial and temporal continuity of the mapping from the reference configuration to the current configuration of the material points. All physical quantities characterizing the continuum are described this way. In this sense, the function  and

and  are single-valued and continuous, with continuous derivatives with respect to space and time to whatever order is required, usually to the second or third.

are single-valued and continuous, with continuous derivatives with respect to space and time to whatever order is required, usually to the second or third.

Eulerian description

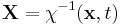

Continuity allows for the inverse of  to trace backwards where the particle currently located at

to trace backwards where the particle currently located at  was located in the initial or referenced configuration

was located in the initial or referenced configuration  . In this case the description of motion is made in terms of the spatial coordinates, in which case is called the spatial description or Eulerian description, i.e. the current configuration is taken as the reference configuration.

. In this case the description of motion is made in terms of the spatial coordinates, in which case is called the spatial description or Eulerian description, i.e. the current configuration is taken as the reference configuration.

The Eulerian description, introduced by d'Alembert, focuses on the current configuration  , giving attention to what is occurring at a fixed point in space as time progresses, instead of giving attention to individual particles as they move through space and time. This approach is conveniently applied in the study of fluid flow where the kinematic property of greatest interest is the rate at which change is taking place rather than the shape of the body of fluid at a reference time.[14]

, giving attention to what is occurring at a fixed point in space as time progresses, instead of giving attention to individual particles as they move through space and time. This approach is conveniently applied in the study of fluid flow where the kinematic property of greatest interest is the rate at which change is taking place rather than the shape of the body of fluid at a reference time.[14]

Mathematically, the motion of a continuum using the Eulerian description is expressed by the mapping function

which provides a tracing of the particle which now occupies the position  in the current configuration

in the current configuration  to its original position

to its original position  in the initial configuration

in the initial configuration  .

.

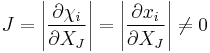

A necessary and sufficient condition for this inverse function to exist is that the determinant of the Jacobian Matrix, often referred to simply as the Jacobian, should be different from zero. Thus,

In the Eulerian description, the physical properties  are expressed as

are expressed as

where the functional form of  in the Lagrangian description is not the same as the form of

in the Lagrangian description is not the same as the form of  in the Eulerian description.

in the Eulerian description.

The material derivative of  , using the chain rule, is then

, using the chain rule, is then

The first term on the right-hand side of this equation gives the local rate of change of the property  occurring at position

occurring at position  . The second term of the right-hand side is the convective rate of change and expresses the contribution of the particle changing position in space (motion).

. The second term of the right-hand side is the convective rate of change and expresses the contribution of the particle changing position in space (motion).

Continuity in the Eulerian description is expressed by the spatial and temporal continuity and continuous differentiability of the velocity field. All physical quantities are defined this way at each instant of time, in the current configuration, as a function of the vector position  .

.

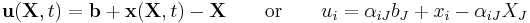

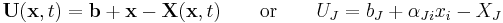

Displacement field

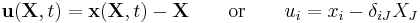

The vector joining the positions of a particle  in the undeformed configuration and deformed configuration is called the displacement vector

in the undeformed configuration and deformed configuration is called the displacement vector  , in the Lagrangian description, or

, in the Lagrangian description, or  , in the Eulerian description.

, in the Eulerian description.

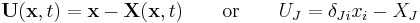

A displacement field is a vector field of all displacement vectors for all particles in the body, which relates the deformed configuration with the undeformed configuration. It is convenient to do the analysis of deformation or motion of a continuum body in terms of the displacement field, In general, the displacement field is expressed in terms of the material coordinates as

or in terms of the spatial coordinates as

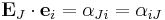

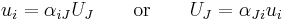

where  are the direction cosines between the material and spatial coordinate systems with unit vectors

are the direction cosines between the material and spatial coordinate systems with unit vectors  and

and  , respectively. Thus

, respectively. Thus

and the relationship between  and

and  is then given by

is then given by

Knowing that

then

It is common to superimpose the coordinate systems for the undeformed and deformed configurations, which results in  , and the direction cosines become Kronecker deltas, i.e.

, and the direction cosines become Kronecker deltas, i.e.

Thus, we have

or in terms of the spatial coordinates as

Governing equations

Continuum mechanics deals with the behavior of materials that can be approximated as continuous for certain length and time scales. The equations that govern the mechanics of such materials include the balance laws for mass, momentum, and energy. Kinematic relations and constitutive equations are needed to complete the system of governing equations. Physical restrictions on the form of the constitutive relations can be applied by requiring that the second law of thermodynamics be satisfied under all conditions. In the continuum mechanics of solids, the second law of thermodynamics is satisfied if the Clausius–Duhem form of the entropy inequality is satisfied.

The balance laws express the idea that the rate of change of a quantity (mass, momentum, energy) in a volume must arise from three causes:

- the physical quantity itself flows through the surface that bounds the volume,

- there is a source of the physical quantity on the surface of the volume, or/and,

- there is a source of the physical quantity inside the volume.

Let  be the body (an open subset of Euclidean space) and let

be the body (an open subset of Euclidean space) and let  be its surface (the boundary of

be its surface (the boundary of  ).

).

Let the motion of material points in the body be described by the map

where  is the position of a point in the initial configuration and

is the position of a point in the initial configuration and  is the location of the same point in the deformed configuration.

is the location of the same point in the deformed configuration.

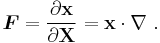

The deformation gradient is given by

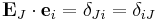

Balance laws

Let  be a physical quantity that is flowing through the body. Let

be a physical quantity that is flowing through the body. Let  be sources on the surface of the body and let

be sources on the surface of the body and let  be sources inside the body. Let

be sources inside the body. Let  be the outward unit normal to the surface

be the outward unit normal to the surface  . Let

. Let  be the velocity of the physical particles that carry the physical quantity that is flowing. Also, let the speed at which the bounding surface

be the velocity of the physical particles that carry the physical quantity that is flowing. Also, let the speed at which the bounding surface  is moving be

is moving be  (in the direction

(in the direction  ).

).

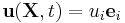

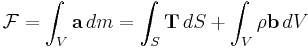

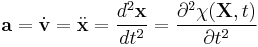

Then, balance laws can be expressed in the general form

Note that the functions  ,

,  , and

, and  can be scalar valued, vector valued, or tensor valued - depending on the physical quantity that the balance equation deals with. If there are internal boundaries in the body, jump discontinuities also need to be specified in the balance laws.

can be scalar valued, vector valued, or tensor valued - depending on the physical quantity that the balance equation deals with. If there are internal boundaries in the body, jump discontinuities also need to be specified in the balance laws.

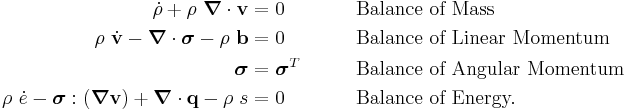

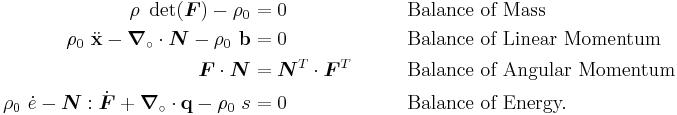

If we take the Lagrangian point of view, it can be shown that the balance laws of mass, momentum, and energy for a solid can be written as

In the above equations  is the mass density (current),

is the mass density (current),  is the material time derivative of

is the material time derivative of  ,

,  is the particle velocity,

is the particle velocity,  is the material time derivative of

is the material time derivative of  ,

,  is the Cauchy stress tensor,

is the Cauchy stress tensor,  is the body force density,

is the body force density,  is the internal energy per unit mass,

is the internal energy per unit mass,  is the material time derivative of

is the material time derivative of  ,

,  is the heat flux vector, and

is the heat flux vector, and  is an energy source per unit mass.

is an energy source per unit mass.

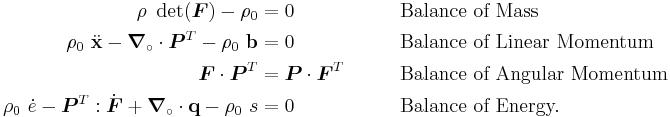

With respect to the reference configuration, the balance laws can be written as

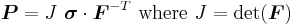

In the above,  is the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor, and

is the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor, and  is the mass density in the reference configuration. The first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor is related to the Cauchy stress tensor by

is the mass density in the reference configuration. The first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor is related to the Cauchy stress tensor by

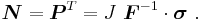

We can alternatively define the nominal stress tensor  which is the transpose of the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor such that

which is the transpose of the first Piola-Kirchhoff stress tensor such that

Then the balance laws become

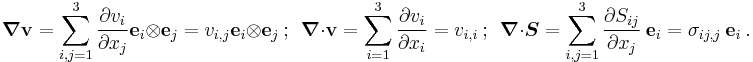

The operators in the above equations are defined as such that

where  is a vector field,

is a vector field,  is a second-order tensor field, and

is a second-order tensor field, and  are the components of an orthonormal basis in the current configuration. Also,

are the components of an orthonormal basis in the current configuration. Also,

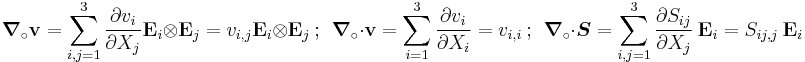

where  is a vector field,

is a vector field,  is a second-order tensor field, and

is a second-order tensor field, and  are the components of an orthonormal basis in the reference configuration.

are the components of an orthonormal basis in the reference configuration.

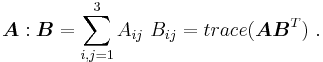

The inner product is defined as

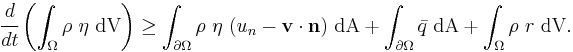

Clausius–Duhem inequality

The Clausius–Duhem inequality can be used to express the second law of thermodynamics for elastic-plastic materials. This inequality is a statement concerning the irreversibility of natural processes, especially when energy dissipation is involved.

Just like in the balance laws in the previous section, we assume that there is a flux of a quantity, a source of the quantity, and an internal density of the quantity per unit mass. The quantity of interest in this case is the entropy. Thus, we assume that there is an entropy flux, an entropy source, and an internal entropy density per unit mass ( ) in the region of interest.

) in the region of interest.

Let  be such a region and let

be such a region and let  be its boundary. Then the second law of thermodynamics states that the rate of increase of

be its boundary. Then the second law of thermodynamics states that the rate of increase of  in this region is greater than or equal to the sum of that supplied to

in this region is greater than or equal to the sum of that supplied to  (as a flux or from internal sources) and the change of the internal entropy density due to material flowing in and out of the region.

(as a flux or from internal sources) and the change of the internal entropy density due to material flowing in and out of the region.

Let  move with a velocity

move with a velocity  and let particles inside

and let particles inside  have velocities

have velocities  . Let

. Let  be the unit outward normal to the surface

be the unit outward normal to the surface  . Let

. Let  be the density of matter in the region,

be the density of matter in the region,  be the entropy flux at the surface, and

be the entropy flux at the surface, and  be the entropy source per unit mass. Then the entropy inequality may be written as

be the entropy source per unit mass. Then the entropy inequality may be written as

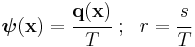

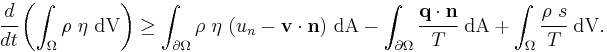

The scalar entropy flux can be related to the vector flux at the surface by the relation  . Under the assumption of incrementally isothermal conditions, we have

. Under the assumption of incrementally isothermal conditions, we have

where  is the heat flux vector,

is the heat flux vector,  is a energy source per unit mass, and

is a energy source per unit mass, and  is the absolute temperature of a material point at

is the absolute temperature of a material point at  at time

at time  .

.

We then have the Clausius–Duhem inequality in integral form:

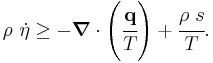

We can show that the entropy inequality may be written in differential form as

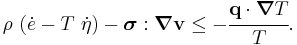

In terms of the Cauchy stress and the internal energy, the Clausius–Duhem inequality may be written as

Applications

See also

- Finite deformation tensors

- Finite strain theory

- Stress (physics)

- Stress measures

- Hyperelastic material

- Cauchy elastic material

- Equation of state

- Theory of elasticity

- Bernoulli's principle

- Peridynamics (a non-local continuum theory leading to integral equations)

- Tensor calculus

- Curvilinear coordinates

- Tensor derivative (continuum mechanics)

- Movable cellular automaton

Notes

- ^ Ostoja-Starzewski, M. (2008). "7-10". Microstructural randomness and scaling in mechanics of materials. CRC Press. ISBN 1-584-88417-7. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=_Qyf1woZPNgC&printsec=frontcover&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ a b Smith & Truesdell p.97

- ^ Slaughter

- ^ Lubliner

- ^ a b Liu

- ^ a b Wu

- ^ a b c Fung

- ^ a b Mase

- ^ Atanackovic

- ^ a b c Irgens

- ^ a b c Chadwick

- ^ Maxwell pointed out that nonvanishing body moments exist in a magnet in a magnetic field and in a dielectric material in an electric field with different planes of polarization. Fung p.76.

- ^ Couple stresses and body couples were first explored by Voigt and Cosserat, and later reintroduced by Mindlin in 1960 on his work for Bell Labs on pure quartz crystals. Richards p.55.

- ^ Spencer, A.J.M. (1980). Continuum Mechanics. Longman Group Limited (London). p. 83. ISBN 0-582-44282-6. http://books.google.com/books?id=AJdfQL0rgrgC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

References

- Batra, R. C. (2006). Elements of Continuum Mechanics. Reston, VA: AIAA.

- Eringen, A. Cemel (1980). Mechanics of Continua (2nd edition ed.). Krieger Pub Co. ISBN 088275663X.

- Chen, Youping; James D. Lee; Azim Eskandarian (2009). Meshless Methods in Solid Mechanics (First Edition ed.). Springer New York. ISBN 1441921486.

- Dill, Ellis Harold (2006). Continuum Mechanics: Elasticity, Plasticity, Viscoelasticity. Germany: CRC Press. ISBN 0849397790. http://books.google.ca/books?id=Nn4kztfbR3AC&rview=1.

- Dimitrienko, Yuriy (2011). Nonlinear Continuum Mechanics and Large Inelastic Deformations. Germany: Springer. ISBN 9789400700338.

- Hutter, Kolumban; Klaus Jöhnk (2004). Continuum Methods of Physical Modeling. Germany: Springer. ISBN 3540206191. http://books.google.ca/books?id=B-dxx724YD4C.

- Fung, Y. C. (1977). A First Course in Continuum Mechanics (2nd edition ed.). Prentice-Hall, Inc.. ISBN 0133183114.

- Gurtin, M. E. (1981). An Introduction to Continuum Mechanics. New York: Academic Press.

- Lai, W. Michael; David Rubin, Erhard Krempl (1996). Introduction to Continuum Mechanics (3rd edition ed.). Elsevier, Inc.. ISBN 978-0-7506-2894-5. http://www.elsevierdirect.com/product.jsp?isbn=9780750628945.

- Lubarda, Vlado A. (2001). Elastoplasticity Theory. CRC Press. ISBN 0849311381. http://books.google.ca/books?id=1P0LybL4oAgC.

- Lubliner, Jacob (2008). Plasticity Theory (Revised Edition). Dover Publications. ISBN 0486462900. http://www.ce.berkeley.edu/~coby/plas/pdf/book.pdf.

- Malvern, Lawrence E. (1969). Introduction to the mechanics of a continuous medium. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc..

- Mase, George E. (1970). Continuum Mechanics. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0070406634. http://books.google.ca/books?id=bAdg6yxC0xUC&rview=1.

- Mase, G. Thomas; George E. Mase (1999). Continuum Mechanics for Engineers (Second Edition ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-1855-6. http://books.google.ca/books?id=uI1ll0A8B_UC&rview=1.

- Maugin, G. A. (1999). The Thermomechanics of Nonlinear Irreversible Behaviors: An Introduction. Singapore: World Scientific.

- Nemat-Nasser, Sia (2006). Plasticity: A Treatise on Finite Deformation of Heterogeneous Inelastic Materials. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521839793. http://books.google.ca/books?id=5nO78Rt0BtMC.

- Ostoja-Starzewski, Martin (2008). Microstructural Randomness and Scaling in Mechanics of Materials. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press. ISBN 9781-1-58488-417-0. http://www.crcpress.com/product/isbn/9781584884170.

- Rees, David (2006). Basic Engineering Plasticity - An Introduction with Engineering and Manufacturing Applications. Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0750680253. http://books.google.ca/books?id=4KWbmn_1hcYC.

- Wright, T. W. (2002). The Physics and Mathematics of Adiabatic Shear Bands. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

![\ \frac{d}{dt}[P_{ij\ldots}(\mathbf X,t)]=\frac{\partial}{\partial t}[P_{ij\ldots}(\mathbf X,t)]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/bc4ad5dc8cc48c7120d0904e76eb8fba.png)

![\ P_{ij \ldots}=P_{ij\ldots}(\mathbf X,t)=P_{ij\ldots}[\chi^{-1}(\mathbf x,t),t]=p_{ij\ldots}(\mathbf x,t)](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/25964e7916ff4deaaa8ec152b21fb4da.png)

![\ \frac{d}{dt}[p_{ij\ldots}(\mathbf x,t)]=\frac{\partial}{\partial t}[p_{ij\ldots}(\mathbf x,t)]%2B \frac{\partial}{\partial x_k}[p_{ij\ldots}(\mathbf x,t)]\frac{dx_k}{dt}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/71c6da260b54c8a9a615b36e2e0a10a1.png)

![\cfrac{d}{dt}\left[\int_{\Omega} f(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dV}\right] =

\int_{\partial \Omega } f(\mathbf{x},t)[u_n(\mathbf{x},t) - \mathbf{v}(\mathbf{x},t)\cdot\mathbf{n}(\mathbf{x},t)]~\text{dA} %2B

\int_{\partial \Omega } g(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dA} %2B \int_{\Omega} h(\mathbf{x},t)~\text{dV} ~.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4da371b65cef69f81e4e16ac2fc1b39e.png)